Notes from the coaching room

‘Flow’ or how to create the conditions for peak performance

The study of organisational leadership often looks to military leaders, explorers, musicians or sportspeople in searching for analogies. This can sometimes go too far - there is something fundamentally different about the wind-blasted slopes of Everest to the workplace on a wet Monday morning in January, for example - but where the comparisons can deliver value is in thinking about individual motivation. The gimlet-eyed focus of a concert pianist or professional sportsperson and the drive that brings them to such peaks of achievement are ripe areas for reflection in our coaching work with leaders. Considering what these peaks of human performance can teach us in the context of leading ourselves and our teams is a fertile source of discussion.

The study of Psychology underwent a major shift at the beginning of the current century. Two American Psychologists, Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, began the school of Positive Psychology by moving the focus of discovery in the science away from diagnosing and treating patients, as it had done since Freud’s pioneering work after the First World War, to considering what could be done to enhance the psychology of individuals and groups in society.

Csikszentmihalyi was particularly interested in motivation. What was it that drove some people to achieve more than others? Through a series of experiments with his students at the University of Chicago, he was able to identify that a high level of work orientation was a better predictor of success than school, home, income or any other environmental factor. In other words, the desire to do well was the best predictor of doing well - intrinsic motivation was a more reliable indicator of success than any extrinsic motivation such as money, power or prestige. This led him to the identification of the ‘autotelic’ personality – one which leads individuals to perform an act for the benefit of the act itself, rather than for any external reward. Subsequent work identified curiosity, persistence and humility as key traits in autotelic individuals.

Further work with these groups led Csikszentmihalyi and his teams of researchers to observe occasions of what sportspeople often refer to as ‘the zone’, describing those times when an individual is completely absorbed in a task to the extent that time passes unnoticed, distractions are easily ignored and even fundamental, physical signals such as hunger or fatigue fail to interrupt the performance in that moment. For sportspeople and musicians, these periods of time are often associated with a higher level of performance than was previously experienced or even foreseen as a long-term opponent is defeated or a previously daunting piece of music is mastered to great acclaim.

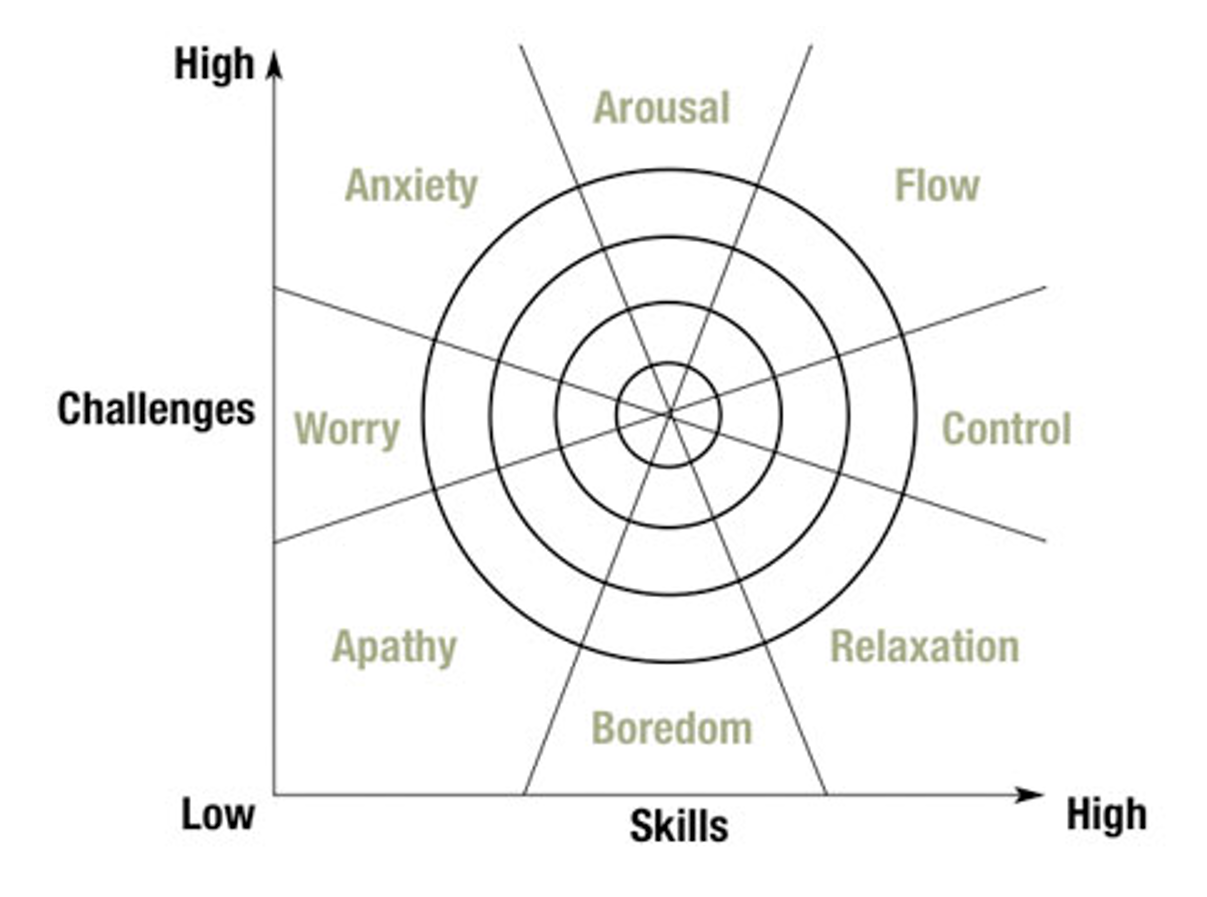

Csikszentmihalyi called this experience ‘flow’ and subsequently identified that it was the balance of high positive challenge and high performance of skills that created the conditions for it to be experienced, as illustrated below:

It’s easy to see how a work environment representing high challenge without the necessary skills to perform would be a source of worry and anxiety, as the diagram illustrates; it’s equally apparent that the absence of challenge or non-utilisation of skills isn’t a happy place for most people to be in their working lives.

We use this discussion in our coaching work to ask leaders to reflect on themselves and their teams, to consider occasions where they may have experienced flow or when they’ve experienced the less positive emotions in the bottom half of the diagram. We wonder together about what they might do to create the conditions where flow is a more regular experience for themselves and the teams they lead.

Things for modern leaders to consider:

- How are you developing your skills? What steps are you taking to build your own skills and those of your teams? Do you have under-utilised skills? Do your teams? What can you do to change that? Are you or anyone in your teams in the lower half of the diagram? When? Why? What can you do about that?

- Do you experience high challenge without believing you have the skills to rise to that challenge? Does anyone in your team? What can you do about that?

Post Script – it took us a long time to get a clumsy Anglo-Saxon tongue around the Hungarian ‘Csikszentmihalyi’. For any reader who is interested and keen to save the hours we spent on it, the phonetic version is ‘Cheeks Send Me High’.

Xytal is the leading British consultancy developing leadership in the health sector. ‘Notes from the coaching room’ is drawn from our real experience of the issues faced by many leaders in improving their leadership practice. Get in contact with us to learn more. If you found this article beneficial, you might also consider checking out our Leadership Development programme.